Home ownership, affordability, retirement, Superannuation

Not financial advice but for discernment and further discussion

NOTE: The below is not financial advice, it is merely for informational and discernment purposes. Please do your own due diligence and consult credentialed financial advice for your specific circumstances. AI has assisted with the research of this article.

Australia currently has a Superannuation Guarantee (SG), which is the mandatory minimum percentage of a worker’s ordinary time earnings that employers must contribute to their employees’ superannuation (retirement savings) fund. Currently 11.5%, but will be raised to 12% from 1 July 2025

The SG was set up in 1992 by the Keating Labor Government to reduce pressure on the Age Pension System which currently costs tax payers circa $52 Billion per year.

It was also designed to improve equity and retirement security as previously only higher income earners and public servants tended to have Superannuation. It also encourages long term financial planning enabling people to accumulate compound returns over decades, with the likelihood of having adequate retirement savings.

The SG has provided a boost to national savings, with some estimates stating Australia’s super system holds over A$3.5 trillion in assets—one of the largest pension pools in the world.

However, in an ABC report from October 2024 they indicate that more Australians are reaching retirement with a mortgage as first home buyers get older.

From the article:

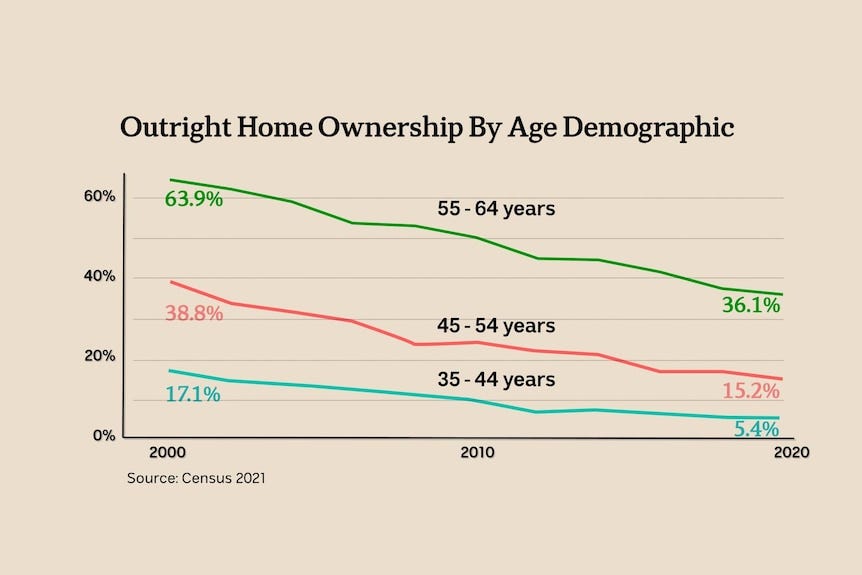

Census data showed over the past 20 years, the number of Australians aged 55 to 64 who owned their homes outright had almost halved.

The average loan balance in this group was about A$190,000, but some owe much more — up to half a million dollars.

This number is likely to drop further with cost of living pressures likely to add to the ability to pay down mortgages quicker, and younger Australians looking down the barrel of higher loans considering the Australian mean dwelling price breaking the million dollar barrier at around A$1,002,500. When you consider that the annual median individual income is around A$41k and median household income is around A$92k, it’s going to be a tough slog for may Australians to ever secure home ownership.

In an article from Professional Planner (Younger Australians anticipate paying off mortgage in retirement), almost a third of working Australians expect to still be paying a mortgage in retirement.

From the article:

When asked about their plan to pay off their mortgage, 38 per cent of Gen Xers said would keep paying their mortgage in retirement, while 18 per cent would consider selling their home to repay their mortgage.

Another 25 per cent said they had plans to use their superannuation to pay off their mortgage in one transaction.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) the average loan size for Australians is around A$660,000 with current interest rates (at time of article release) sitting at around 6%.

That equates to a monthly repayment of A$3,957 per month, over 30 years the interest on this without additional payments would be around A$764K or a total amount of A$1.4 million over the life of the loan.

Based on the median household income, that repayment equates to more than 50% of the household income going towards the mortgage. To put this into perspective, house stress is commonly defined as spending 30% or more of income on housing.

These trends aren’t likely to slow down any time soon due to multiple contributing factors, which I’ll outline further down, but backed up by South Australian Lending Adviser Michael Arbon in a response to Premier of Queensland. 👇

But for now lets get back to the Superannuation Guarantee. As mentioned above the Aged Pension is currently costing tax payers circa A$52 Billion annually, with some estimates predicting this to stay somewhat the same into the next few decades, supposedly due to more Australians becoming self funded under the SG.

But some contributing factors which could prevent the current annual amount not being stable, but instead likely to increase by tens of billion, are:

1. Low Super Balances at Retirement

Many workers—especially women and low-income earners—retire with insufficient superannuation to fund their retirement.

As of 2023:

Median super balances at retirement were ~$180,000 for women, and ~$270,000 for men.

Far below what’s needed to be self-funded (ASFA recommends ~$595k for singles for a "comfortable" retirement).

Causes:

Part-time/casual work

Career breaks (e.g., childcare)

Inconsistent contributions

Super not paid on paid parental leave or some gig economy work

2. Heavy Reliance on Housing Wealth

Many older Australians are "asset rich, income poor"—owning a home but having limited income-producing assets.

The family home is exempt from the Age Pension asset test, disincentivizing downsizing or drawing on that equity.

Result: People may qualify for a part or full pension even while sitting on millions in home equity.

3. Cost-of-Living & Housing Affordability Crisis

Rising housing, energy, and health costs make it harder to save during working life.

Younger Australians are entering the workforce later, accumulating debt (e.g. HECS/HELP), and struggling to enter the housing market.

This delays or reduces super contributions and asset building.

4. Longevity Risk & Uncertainty

Australians are living longer, but many don’t have enough saved to last 25–30 years in retirement.

Uncertainty around:

Life expectancy

Health care costs

Future economic conditions

Leads many to underspend in retirement and rely on the Age Pension as a safety net.

5. Structural Policy Gaps

Super not universal for all workers (e.g., many contractors and gig workers miss out).

Contribution caps (e.g., $27,500/year) limit catch-up potential for older workers.

No SG on paid parental leave → disproportionately affects women.

6. Gender Super Gap

Women retire with ~30–35% less super than men due to:

Unpaid caregiving roles

Fewer years in the workforce

This entrenches pension dependence for many women, especially single women in retirement.

7. Inequitable Tax Concessions

Super tax concessions disproportionately benefit high-income earners, who are already more likely to be self-funded.

Low- and middle-income earners receive relatively small tax benefits, limiting compounding growth potential.

That’s some list, but below are some of the SG reforms being offered up to combat these, which include:

Pay super on parental leave to help close the 30–35% gender gap in retirement balances.

Include More Workers (Gig, Contractors, Low-income), remove outdated income thresholds and extend SG to all workers, regardless of status.

Consider gradual increases to SG to 13–15%, with trade-offs to avoid wage suppression.

Cap or taper concessions for high earners (e.g., start taxing contributions at 30% above $300k).

Incentivise Downsizing. expand downsizing contribution incentives, remove stamp duty barriers.

Include high-value homes above a generous threshold (e.g. $2–3 million) in the means test.

Mandate clear, personal projections in super statements.

Offer tax and welfare incentives for older workers to remain in part-time work.

Allow pensioners to earn more without losing payments too quickly (e.g., raise Work Bonus).

Depending on how moderate or strong the reforms listed above are adopted, it is estimated they could equate to circa A$10 to A$25 billion in savings to the Governments (i.e. tax payers) financial burden for Aged Pension costs annually, in the hope of avoiding the tax concession costs outpacing the cost of the Aged Pension.

The tax concessions mentioned at point 7 currently equates to circa A$50 Billion to A$60 Billion back to tax payers (well some anyway), which supposedly offsets the cost to ALL tax payers for the Aged Pension. So you see, as also mentioned in point 7 these concessions benefit primarily higher income earners who are already more likely to be self-funded and can afford to make additional contributions, with the likelihood of leading to the cost of future tax concessions exceeding the cost of the Aged Pension.

In the lead up to the 2025 Federal Election, Gerard Rennick from People First had a policy stance on the SG, and although Gerard believes the compulsory SG should be abolished and made voluntary, personally, having had SG for most of my working life I like the idea of a structured savings mechanism, so would likely still look at it if it was made voluntary. In saying that I do believe there should be more flexibility in being able to utilise the funds to benefit workers during their life prior to retirement.

One concept I’ve been bouncing around for some time is an Owner Occupied Self Managed Super Fund (OOSMSF), I even put a little demo video together for it about 5 years ago.

If you haven’t got 12 minutes to watch the video, here is a quick summary

Owner-Occupied Self-Managed Super Fund (SMSF) with Offset Concept

This hypothetical financial structure explores allowing Australians to use their superannuation savings—held within a Self-Managed Super Fund (SMSF)—to purchase and live in their own home, while leveraging a mortgage offset account linked to the SMSF.

Key Features:

SMSF owns a portion of the home you live in, structured under strict compliance rules (currently prohibited under existing super laws).

The SMSF mortgage has an offset account, which reduces interest payable by offsetting the loan balance.

Employer super contributions (and optionally, salary sacrifice) are paid directly into this offset account.

Existing super balances (e.g., $250,000) can be transferred into the SMSF and immediately reduce interest from day one.

Modeled Benefits:

Interest savings can exceed $600,000–$700,000 depending on contributions and initial offset.

Loan terms can reduce from 30 years to as little as 13 years in ideal scenarios.

After loan payoff, ongoing super contributions accumulate as per normal depending on investment strategies.

Lets have a look at some scenarios using the figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) average loan at A$660,000 with current interest rate at 6%, to see what this could like like.

Scenario 1. Standard Mortgage (No Offset)

Mortgage: $660,000

Interest Rate: 6%

Term: 30 years

Total interest paid: ~$766,000

Total repayments: ~$1,426,000

Loan fully paid after: 30 years

Scenario 2. Mortgage with SMSF Offset Facility

Offset account is credited $2,500/month = $30,000/year

Offset account balance grows and reduces interest charged, thereby accelerating repayments even though the official term is 30 years.

This simulates the effective reduction in interest as the offset account grows and assuming we redirect the interest savings into extra repayments, accelerating the payoff.

SMSF Offset Mortgage Results

Loan paid off in: ~20 years

Interest saved: ~$310,000

Total interest paid: ~$456,000

Total repayments: ~$1,116,000

Time Saved on Mortgage:

~10 years earlier

Interest Saved Compared to No Offset:

~$310,000

Lets have a look what it looks like with a spouse but no additional voluntary contributions.

1. Standard Mortgage (No Offset)

Loan: $660,000

Interest rate: 6%

Term: 30 years

Monthly repayment: ~$3,958

Total interest paid: ~$766,000

Total repayments: ~$1,426,000

Loan paid off: 30 years

2. SMSF Offset Mortgage (Employer Contributions Only)

With $1,437/month going into the offset account:

Offset balance grows steadily.

Reduces monthly interest cost.

Assume you redirect the interest savings into extra repayments.

Results

Loan paid off in: ~24 years

Total interest paid: ~$595,000

Interest saved vs standard: ~$171,000

Total repayments: ~$1,255,000

Some more detail:

If you had a $600,000 mortgage and brought $200k in via OOSMSF off set, you may still have the original loan under your name. (there would need to be discussions and rules around redraw etc.)

A possibility is to look at the OOSMSF taking over the whole loan and then locked in until retirement.

You could still sell and upgrade/downgrade, but the money/asset

would be preserved under the OOSMSF until retirement.

Now as I stated in the beginning, this article is ‘ for discernment and further discussion’ and I’d actually appreciate peoples views on issues that would hold this concept back so I can do some more research on viability, I know Lenders and Industry Superannuation Funds wouldn’t be happy for starters.

But it’s also an opportunity to promote discussions about other solutions.

The sad reality is though, even if the OOSMSF concept was adopted in some form, as a nation we still have many more hurdles to overcome in regards to housing access and affordability. Because even if people had access to their Super to use for property, it would possibly still burden the access and cost to housing even further unless we address the issues listed below.

1. Limited Housing Supply

Zoning restrictions & planning delays: Local councils and state governments often impose restrictive zoning laws, limiting higher-density developments, especially in established suburbs.

Slow construction pipeline: Labour shortages, high material costs, and rising interest rates have slowed new home construction.

Land release constraints: Limited release of land for development, especially near major cities, restricts supply.

2. Increased Demand

Population growth & migration: High levels of international migration, particularly post-COVID, have sharply increased housing demand, especially in major cities.

Household formation trends: More people living alone or in smaller households (e.g., post-divorce, aging populations) increases the number of dwellings required.

Speculation & investor demand: High investor activity in the market, particularly during low interest rate periods, has inflated prices.

3. Financial & Tax Incentives

Negative gearing & capital gains tax discount: These tax settings disproportionately benefit property investors, incentivising housing as a speculative asset over productive use.

Low interest rates (historically): Cheap credit from 2010–2022 enabled buyers to take on larger loans, inflating property values.

First home buyer grants/stimulus: While intended to help, these often push up prices in entry-level segments rather than improving affordability.

4. Government Policy Failures

Lack of national coordination: Housing policy is fragmented across local, state, and federal levels, often lacking cohesion.

Insufficient social and affordable housing investment: Long-term underfunding has led to growing waitlists and greater pressure on the private rental market.

Urban planning mismatches: Policies often fail to match housing development with necessary infrastructure (transport, schools, services).

5. Socioeconomic & Demographic Pressures

Wealth inequality: Those with family support or existing property assets benefit from intergenerational wealth transfers, exacerbating inequality.

Rent increases: Rising rents reduce the ability of people to save for a deposit, keeping them trapped in the rental cycle.

Aging population: Older Australians tend to hold onto large family homes longer, reducing turnover in established suburbs.

I don’t have the complete answers, but the more people who are aware of the problems, the more we can encourage discussion and debate for a better path forward.

It just seems the entrenched legacy political parties are not interested in better solutions, and for them it seems like it’s just business as usual, throwing other peoples money at the issue, rather than reducing government (tax payer) debt and creating an environment for affordable access to housing.

Thanks for reading.

And just for a quick promotion, if like me, you are tired of the current batch of politicians, the electoral system and shortcoming in our constitution, check out Australians For Better Government, their recently released Prospectus, and if you like what you see consider getting involved.

Mark

COI Disclosure: Mark Neugebauer is a Member of the Board for Australians for Better Government.

Disclaimer: All content is presented for educational and/or entertainment purposes only. Under no circumstances should it be mistaken for professional advice, nor is it at all intended to be taken as such. The contents simply reflect current newsworthy items for many varying topics that are freely available. It is subject to error and change without notice.

Neither this Substack nor any of its principals or contributors are under any obligation to update or keep current the information contained herein.

Although the information contained is derived from sources which are believed to be reliable, they cannot be guaranteed.